CASUS case scenarios can be used in a blended learning environment and can lead to questions and discussions in the classroom.

CASUS can also be of beneficial use in the classroom to stimulate discussions.

The concept of the virtual patient helps autodidactic students to get a deeper, more practical understanding of patients.

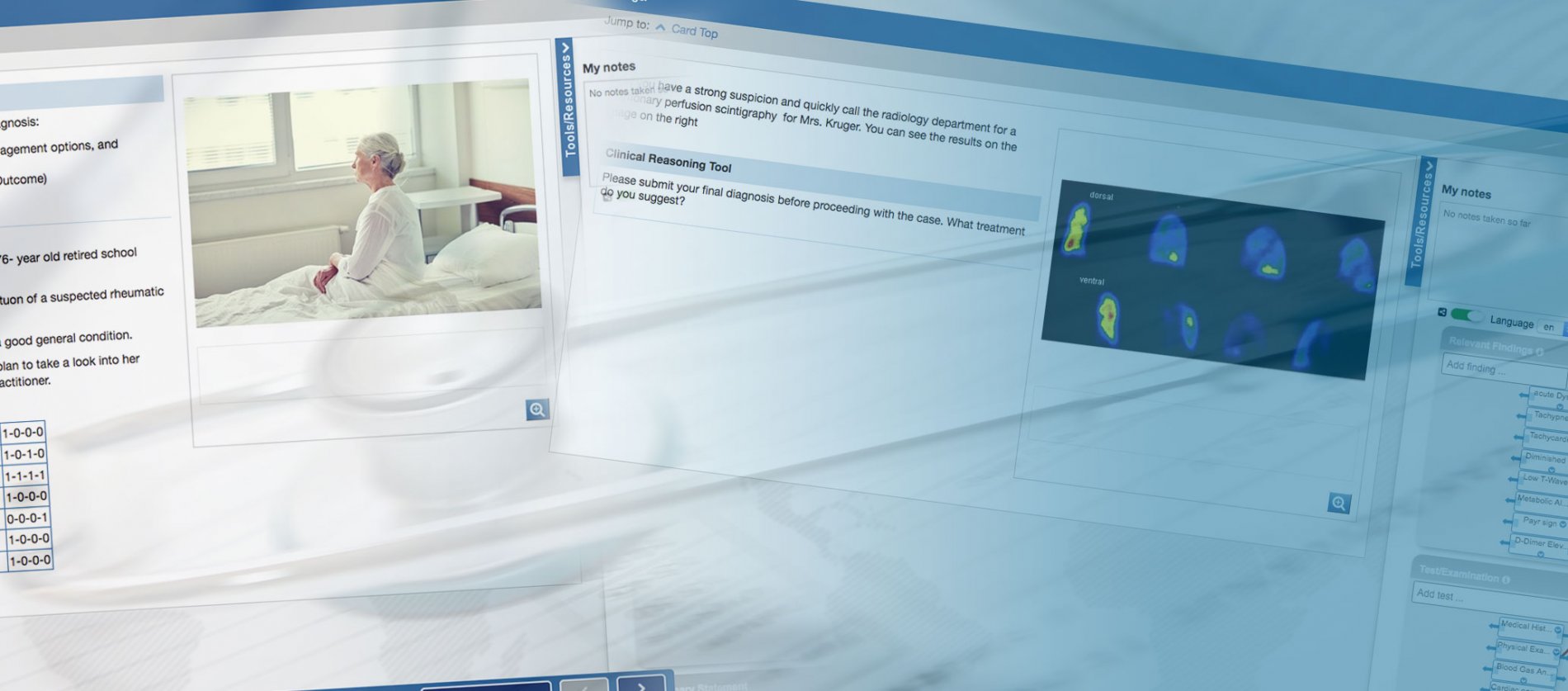

You can use CASUS to describe real cases. The linear sequence of the patient’s story helps impart knowledge.

A right answer backed by a clear and precise clarification is vital for writing good virtual patient cases. Leaving answers unexplained can lead to frustration among students.

Our on-going cooperation with various educational institutions in the more than 20-year history of CASUS keeps us up to date with the current level of didactic competence.

The CASUS online education system emerged from a collaboration of medical doctors, media educators and computer scientists. CASUS allows virtual patient cases to be created and presented to students. Virtual patients are not a substitute for real-life patients and bedside teaching, but they can be a valuable addition to both preparation and follow-up and help to make clinical reasoning tangible at an early stage.

The advantages of an online education system as compared to classroom teaching are evident: virtual patients can be accessed anytime and anywhere. In the classroom, real patients may not always be readily available.

The virtual patients presented in CASUS can be used in many didactic areas of application (see literature). The duration of each learning unit can be personalized. You can write long cases that take up to 45 minutes, or short “key feature” cases that take less than 20 minutes and which focus on the most important decision-making points regarding key symptoms, whereby clinical reasoning is conveyed in both types of cases.

CASUS cases are seen as low-fidelity and are not simulations. Authors can enhance their cases by adding multimedia material, such as images and audio and video files. However, we recommend putting more emphasis on the case storyboard and learning objectives, as this has a greater influence on students’ learning success than elaborate multimedia material.

A comprehensive collection of virtual patients can help the student learn and also study through repetition. In self-learning scenarios, the cases should focus on giving students feedback and explaining in more detail.

Preparatory cases can keep questions open, which can then be discussed in the classroom. Lecturers can also look at the entries that the students made in the prep cases and use them to discuss the answers and possibilities more intensely in the classroom (learning analytics).

CASUS cases can also be worked on together as a group in a classroom. In this case, CASUS can be used as a voting system in which participants give their answers, the results can then be viewed immediately, and the solution can then be discussed within the group.

Most cases in CASUS are linear in that the case storyboard is the most important aspect of the case. This allows every student to impart the same knowledge. The students answer the same questions and, in the process, use our self-developed interactive clinical decision-making (clinical reasoning) tool. Due to the linear structure, the scope of the learning units can be estimated and thus easily embedded in the curriculum.

CASUS also supports complex navigation. Skipping ahead allows students to deliberately leave out content, if they wish to do so. Decision-making techniques can also be implemented with this approach.

One of the most important aspects of self-learning is the expert feedback: in our training sessions, we emphasize again and again that it is extremely important to precisely justify an answer and why the expert chose that answer as the correct one, and, vice versa, why the other options are false. If this is not entirely clear, it can be discussed in the answer comment. Clinical reasoning can thus be made tangible directly in the case. The answer comments can also be supplemented by links that lead to more detailed information and encourage self-learning. Care should be taken to ensure that additional content is manageable and can be dealt with realistically as part of the integration into the curriculum.

Certain question types also allow students to give free-text answers without further specifications. Lecturers can evaluate these answers individually and give their students personal feedback. This strengthens the interaction between teacher and student.